Adaptation is a strange animal. How stories come to be presented in general can be an odd process, especially in modern times where collaboration and the lending of ideas from one writer to another is common. Or when you consider that most film scripts these days pass through not one or two writers, but usually upwards of six to ten in a “writer’s room”. It’s not uncommon for studios to bring in well-known comedians to “punch up” family, animated and comedy scripts to get the most laughs per minute. Heck, before a script can even be adapted into a novelization, it has often already been adapted from a previous screenplay, that was adapted from a pitch, that was cribbed from a novel. But even when you streamline this process to its most simplest and just consider who receives final credit for stories, sometimes there are still more versions of a story at the end of the day than we realize. This process can be so strange that it’s led to a weird, yet kind of wonderful sub-genre of movie novelizations, the novel based on a script, which was in turn originally based on a novel. From book to screen back to book again. Like a twisted version of the whisper game, the ideas that an author puts to paper can sometimes take some fascinating turns when adapted to the screen and then re-adapted to a new novel. Here are some of our favorite instances of book to screen to book…

First up, let’s take a look at Who Goes There?, the celebrated science-fiction novella by John W. Campbell Jr. (written under the name Don A. Stuart) was first published in the pages of the pulp magazine Astounding Science-Fiction in 1938. Not only was the story popular, being reprinted many times over the last 80 years, it was also heralded as one of the finest science-fiction stories ever written (as voted on by the Science Fiction Writers of America in 1973) and has proven to be hugely influential in the genre inspiring a multitude other stories (including Invasion of the Body Snatchers and Alien) and the story has been the subject of many adaptations in other mediums. Most notably, the story was adapted into a 1951 film called The Thing From Another World, which was then in turn adapted by Bill Lancaster and John Carpenter into the hugely influential 1982 film The Thing. Then, in the same year, as with most of Carpenter’s early film work, the movie was adapted into a novelization, in this instance by famed science-fiction author Alan Dean Foster.

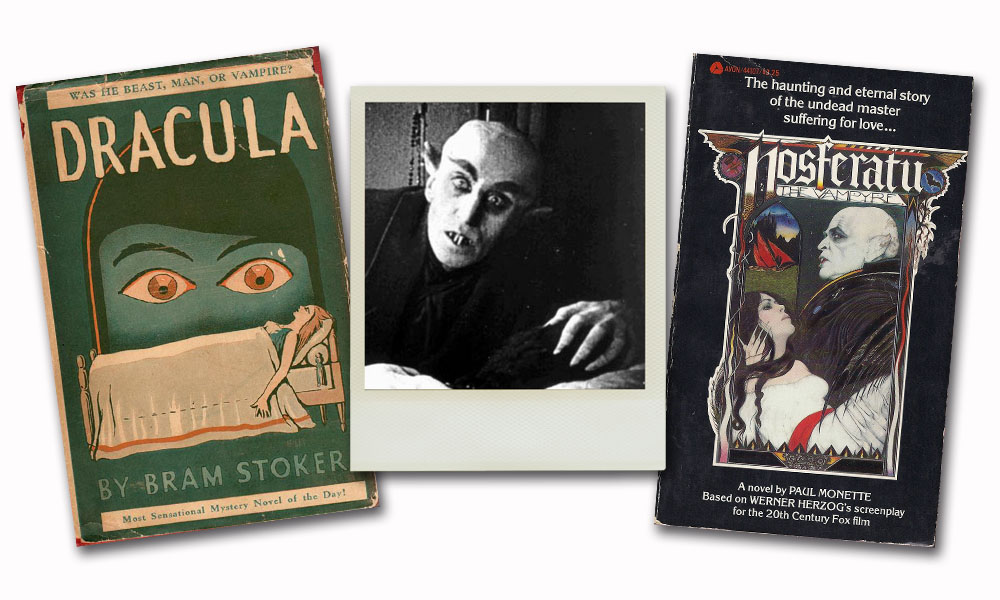

Shifting gears from classic sci-fi to classic horror, there’s the strange case of Bram Stoker’s Dracula. First published in 1897, Stoker’s gothic masterwork detailing the later years of Count Dracula has spawned so many imitations and adaptations that it’s hard to keep count (pun fully intended.) In fact, in 1922, German expressionist director F. W. Murnau and scriptwriter Henrik Galeen unofficially adapted the book into one of cinema’s first full-length horror films titled Nosferatu: A Symphony of Horror. Though we’ve never heard of a specific novelization of the 1922 Nosferatu, we wanted to bring it up as that film was later used as the inspiration and basis for Werner Herzog’s dramatic remake, Nosferatu the Vampyre, which was novelized by Paul Monette (who we’ve mentioned on the site before for his rich work adapting the 80s crime epic Scarface.) So, in a manner, Stoker’s Dracula was adapted into two films (unofficially), one of which was then adapted into a novelization.

But if that connection is too disjointed for your tastes, consider the very strange case of Francis Ford Coppola’s 1992 official adaptation of the original 1897 novel, Bram Stoker’s Dracula. At the time there was a lot of press surrounding the film lauding it for its celebrity cast, the ingenious in-camera special effects work, and the fact that even though there was a screenplay written by James V. Hart, Coppola was fond of having copies of the book available on set so that the actors could read direct passages from the novel. Considering that the birth of the novelization lay in the chicanery of having a film associated with a best selling book (a la The Godfather or Jaws), one would think that having such a famous work of fiction, probably the most well-known horror novel ever written, as the basis for a movie would be enough to help drive advertising and ticket sales. Apparently it wasn’t as American Zoetrope partnered with Signet Publishing to commission the novelization of the film by Fred Saberhagen & scriptwriter James V. Hart. So in 1992 copies of Bram Stoker’s Dracula, based on the script of the film, based on Bram Stoker’s Dracula was released to the public. If Stoker wasn’t already turning in his grave over F. W. Murnau stealing his work for the cinema, he was most assuredly trying to crawl out of his coffin and become a creature of the night to question American Zoetrope about the sanity of their advertising department.

With the modest success of his 1992 Dracula adaptation, Francis Ford Coppola and his American Zoetrope sought to expand their catalog of gothic horror to include a similar themed adaptation of Mary Wollstonecraft Shelley’s 1818 novel Frankenstein. Adapted by up and coming auteur filmmaker and scriptwriter Frank Darabont and directed by Kenneth Branagh, Mary Shelley’s Frankenstein shambled its way onto theater screens in 1994. In a very similar turn of events to Dracula, American Zoetrope partnered with Signet publishing, this time hiring famed novelization author Leonore Fleischer to pen the adaptation of an adaptation. Though the film was roundly panned by critics and shunned by theater goers, the novelization has a fair amount of fans. This might be because the novel was based on Darabont’s script, which has a vastly different tone and feel than the final film. Darabont has been quoted as saying (and we’re paraphrasing) that his aim with the script was to capture the subtleties of Shelley’s original novel, something that Branagh failed to translate to screen.

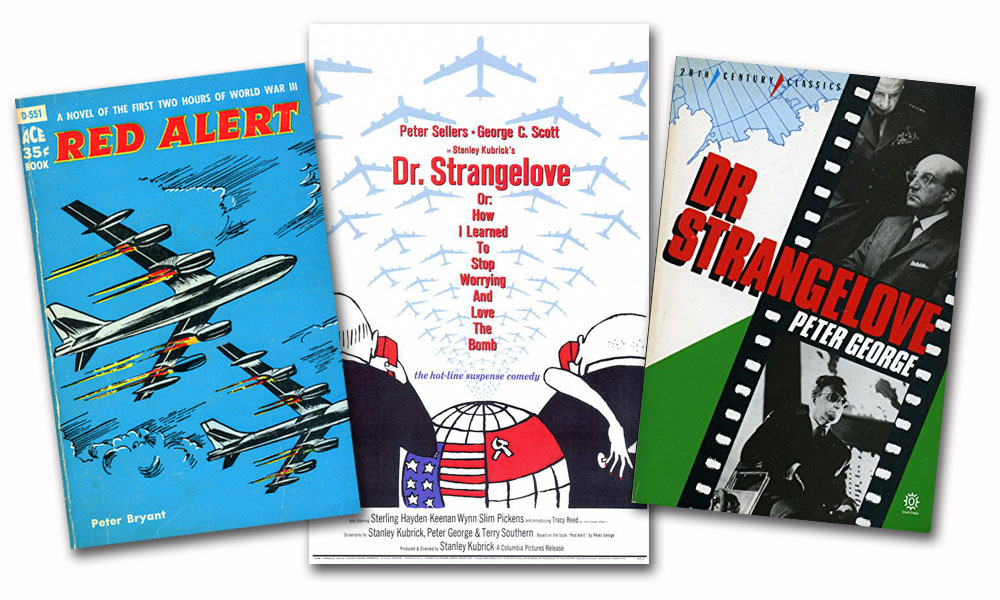

Sometimes these weird adaptations of adaptations actually involve the authors of the original novels. One that springs to mind is the case of Stanley Kubrick’s 1964 film Dr. Strangelove or: How I Learned to Stop Worrying and Love the Bomb. The script was written by Kubrick and co-writer Terry Southern, but they also invited novelist Peter George to the production as they were adapting his 1958 novel Red Alert (originally published in the United Kingdom as Two Hours to Doom under the pseudonym Peter Bryant.) George’s original novel was vastly different than what the trio would end up writing for the script, though the core ideas were still intact. Apparently George had enjoyed the process enough that he would pen a faithful novelization of the film in 1988, 24 years after the movie hit cinemas.

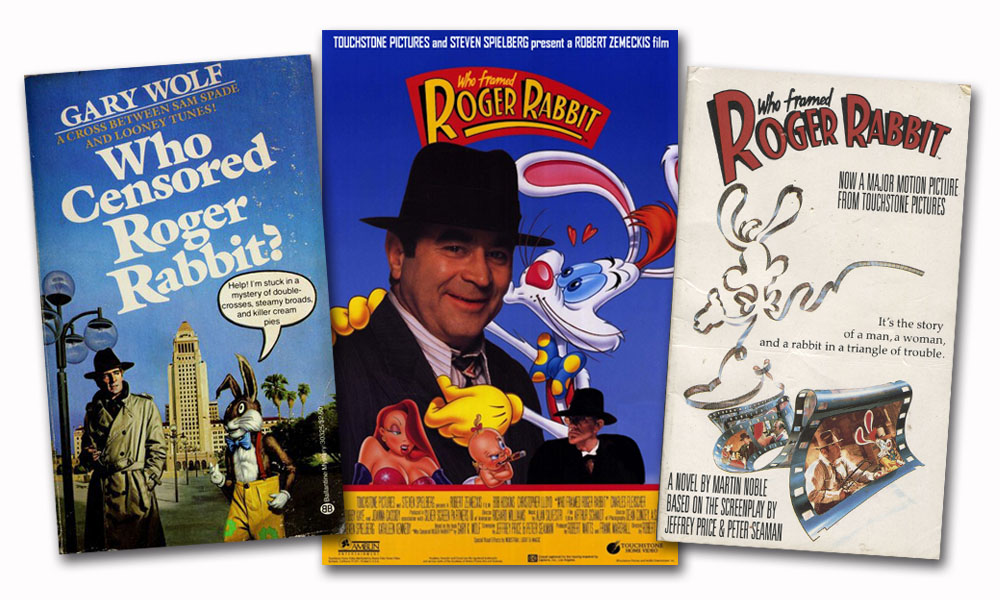

The last set we wanted to mention in this book to screen to book set of weird adaptations is Gary K. Wolf’s seminal 1981 work, Who Censored Roger Rabbit. The novel was the basis for Robert Zemeckis’ Disney film Who Framed Roger Rabbit? Though the original novel is a tad nit darker than the eventual film, it’s plain to see why Zemeckis chose this as his follow-up to Back to the Future. Having just scored his mega hit at the box office, he wanted to stretch his legs a bit and tackle something that was much larger in scope. Crafting a world that was an even mix of live action and zany 40s-style animation was still pretty ambitious for the late 80s, and Wolf’s novel that mashed up newspaper comic strips and the real world seemed like a perfect work to adapt. Seeing as it was produced by Disney though, you can imagine that they didn’t want to simply re-released Wolf’s original as a tie-in with a movie accurate cover as it’s aimed at a more adult audience and has a fairly different plot. Instead they partnered with Star Books and commissioned author Martin Noble to adapt the story into a new novelization that was more in-line with the plot of the film. Strangely though, it seems that the novel was never released in the United States, instead it was published for the UK market.