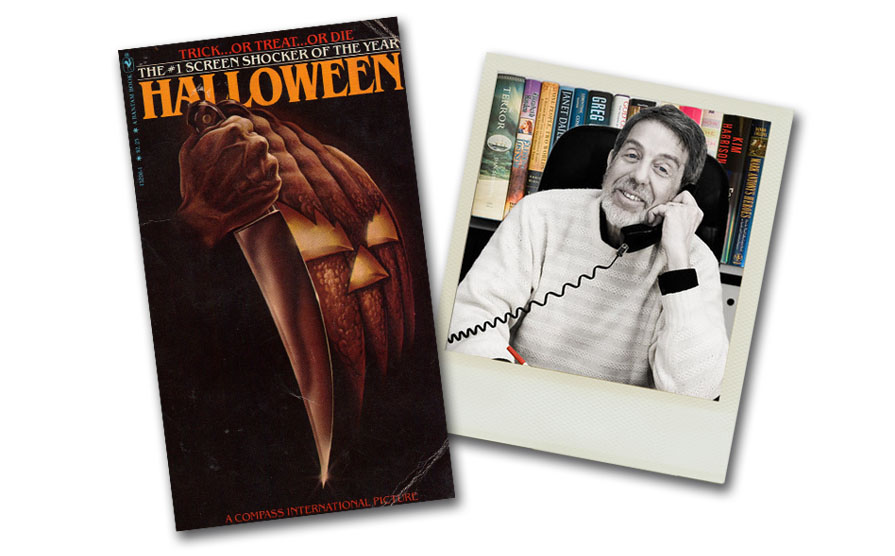

Movie novelizations are such a niche subset of publishing (that is pretty criminally under-examined), that it’s rare to find much in the way of articles detailing the “inside baseball” aspects of the industry. We were recently pointed to this piece written by Richard Curtis, literary agent, author and frequent novelizer who wrote one of the most sought after novelizations, the adaptation of John Carpenter’s original Halloween. In a refreshing turn, Curtis (who wrote under the pen name Curtis Richards) shares some insight into the process of how a novelization comes to be…

Novelizations of movies and television shows are among the most intriguing subspecies of commercial fiction. I say subspecies because they obviously cannot be spoken of in the same breath as The Magic Mountain or Portrait of a Lady; indeed, even commercial novelists look down their noses at novelizations as possessing not a shred of redeeming social value, as the literary equivalent of painting by numbers. On the spectrum of the written word, tie-ins are as close to merchandise as they are to literature.

Tie-ins are kin to souvenirs, and in some ways are not vastly different from the dolls, toys, games, calendars, clothes, and other paraphernalia generated by successful motion pictures and television shows. Those who write them usually dismiss them with embarrassment or contempt, or brag about how much money they made for so little work. Yet, when pressed they will speak with pride about the skill and craftsmanship that went into the books and assure you that the work is deceptively easy. And if you press them yet further, many will puff out their chests and boast that tie-in writers constitute a select inner circle of artisans capable of getting an extremely demanding job done promptly, reliably, and effectively, a kind of typewriter-armed S.W.A.T. team whose motto is, “My book is better than the movie.”

Read the full article on the Curtis Agency site.