We recently stumbled upon a very interesting article in the New York Times that ran back in the summer of 1981 which talks about the then current state of the movie novelization market. It’s rare to find articles centered on the subject in general, but even rarer to find one that digs into the behind-the-scenes sales, author advances, and licensing numbers. We’ve always been fascinated by the financial information associated with pop culture, be it the box office figures of movies, or the sales goals of publishers that determine success or failure for book releases. This piece, titled Publishers Turing Cool to the Tie-In Novelization of Movies and written by

Aside from the illumination of some of the murky behind-the-scenes business aspects to this piece, what we really found interesting is the overall perspective that the industry had towards novelizations at that specific moment in time. In a nutshell, various sources are on record stating that the genre is dying as evidenced by the shrinking of author’s advances and licensing costs. The bottom line being that if publishers aren’t willing to spend hundreds of thousands of dollars to take on these novelization projects, then there is a problem. With the benefit of hindsight it’s interesting to see fear in the industry right before a very large boom in eventual output. Sure, the individual movie tie-in novelizations that would come in the 80s weren’t breaking into the millions-sold category for the most part (E.T. and his Adventures on Earth being a notable exception), but there were a lot of books that would sell 100K copies, and with cheaper up-front costs the publishers could turn out a lot more projects simultaneously. So profits would probably stabilize from what they were seeing in the 70s. This lack of faith before the boom reminds me a lot of what we were seeing in the film industry towards the end of the 80s and again today in the 2010s. The moral of the story? Every project does not need to be a hulking juggernaut in order for the industry to succeed.

“One thing publishers have painfully learned in the last few years is that it is the kind of movie – rather than the success of the movie – that causes people to pay their $2.50 or $2.95 for a slim volume of slightly over 200 pages. Richard Pryor’s ‘Bustin’ Loose’ was passed over this summer, as was Mel Brooks’ ‘History of the World, Part I,’ because novelizations of comedies do not sell. Mr. Pevers was able to persuade Bantam to pay $50,000 for ‘9 to 5’ because Jane Fonda, Dolly Parton, and Lily Tomlin would be pictured on the cover. ‘9 to 5’ has earned more than $100 million at movie theaters in the United States and Canada; the novelization sold barely 150,000 copies.”

We suggest heading over to the New York Times archive to read the piece, though we found the site buggy and the article wouldn’t always populate properly, so it’s also included below.

PUBLISHERS TURNING COOL TO THE TIE-IN NOVELIZATION OF MOVIES (by

LOS ANGELES – Turning movies into successful books is a tricky business. A few years ago, Bantam, Dell, Ballantine, Warner Books and half a dozen other paperback houses were offering hundreds of thousands of dollars for screenplays they could transmute into novels. Today, the average price paid for a movie is $25,000. Such recent box-office successes as ”Bustin’ Loose” and ”The Four Seasons” never even got a nibble from publishers.

“We were all getting burned,” says Fred Klein, executive editor at Bantam, who describes the novelization of “F.I.S.T.” as the “Heaven’s Gate'” of movie novelizations – the expensive disaster that sent the first psychological chills through the industry.

“F.I.S.T.'” – which starred Sylvester Stallone as a labor leader modeled on Jimmy Hoffa – was bought by Dell for $400,000. “It was $400,000 down the drain,” says Mr. Klein, who is equally quick to wince at the $100,000 his own company paid for the novelization rights to “The Main Event,” a Barbra Streisand-Ryan O’Neal boxing movie. “With embarrassing results,” he adds.

After a few more major failures -including “Ode to Billie Joe,” for which Dell paid $250,000, and “The Rose,” which Warner Books bought for $246,000 – the bottom dropped out of what publishers call “the movie tie-in market.”

Can’t Figure Out Loss

Mark Pevers, who licenses books for 20th Century-Fox, still shakes his head at the failure of “The Rose,” which sold considerably fewer than 100,000 copies and lost Warner Books nearly all of its $246,000. “The movie was good; Bette Midler got an Academy Award nomination, and the novelization by Leonora Fleischer was great,” says Mr. Pevers. “Why didn’t it sell?”

Novelizations started as a merchandising tool approximately 15 years ago. “The studio publicity departments got a hack to grind out a book which was given to a publisher as a way of getting the movie’s art in front of the public,” says Annette Welles, vice president of publishing at MCA, the parent company of Universal Pictures. There were a few early successes such as “2001: A Space Odyssey” and the Bantam screenplay of “Butch Cassidy and the Sundance Kid.”

Rush Began in 1976

However, the big rush to novelizations didn’t begin until 1976 when “The Omen” sold more than one million copies. “Suddenly there was a book which sold independently of and long after the movie,” says Miss Welles, who is Mr. Pevers’s counterpart at Universal. By the time “Jaws 2” had also sold over a million copies and “Star Wars” had sold over 3.5 million, “publishers were dazzled by Hollywood flash,” she adds. And studios were holding the kind of bidding auctions that are usually reserved for hard-cover best sellers.

The high price paid by publishers, plus the glut of books, meant disaster. There was one additional problem. The life of an ordinary paperback is four or five weeks. Because most movies are bunched together at Christmas and in the summer, most novelizations were battling one another in supermarket racks at the same time.

One thing publishers have painfully learned in the last few years is that it is the kind of movie – rather than the success of the movie – that causes people to pay their $2.50 or $2.95 for a slim volume of slightly over 200 pages. Richard Pryor’s “Bustin’ Loose” was passed over this summer, as was Mel Brooks’ “History of the World, Part I,” because novelizations of comedies do not sell. Mr. Pevers was able to persuade Bantam to pay $50,000 for “9 to 5” because Jane Fonda, Dolly Parton, and Lily Tomlin would be pictured on the cover. “9 to 5” has earned more than $100 million at movie theaters in the United States and Canada; the novelization sold barely 150,000 copies.

Horror Genre Selling

According to Miss Welles, “The horror genre is the only one publishers are currently interested in. The straight novelization is dead.”

Where comedies and love stories fail as novelizations, horror and fantasy films do extremely well, even when the movies that are novelized were failures at the box office. Despite the poor early returns on Paramount’s “Dragonslayer” Ballantine’s novelization is selling briskly. Perhaps the prime example is Universal’s “The Legacy.” The film earned a poor $5 million in film rentals; the book sold more than one million copies in the United States and was extensively licensed abroad. Nearly every new horror film from “The Fun House” to Universal’s remakes of “Cat People” and “The Thing” has found a publisher.

David Rottman of Ballantine is one editor who is not limiting his purchases to horror movies. “If a movie has some literary bent and you pay $25,000 for an intelligent, well-done book, you can do really well,” he says. “We did nicely with ‘Brubaker’ – injustice in prison with a Hollywood twist. We sold over 200,000 copies of ‘The Elephant Man.’ That movie left a hunger in moviegoers for more information; no movie totally fleshes out a character like a book can.” Adds Miss Welles, “The object in novelizations is to reflect the movie but go beyond.” Most publishers are looking for well-written novelizations that can stand on their own as books.

What Novelizers Earn

Christine Sparks, the novelizer of “The Elephant Man,” did months of research. Novelizers – who are no longer studio hacks – are paid an advance of $5,000 to $50,000, plus a very small royalty. The average advance is $10,000. As in most fields, there are stars. Among those in demand are Miss Fleischer, who is now turning 20th Century-Fox’s homosexual love story, “Making Love,” into a novel; Alan Dean Foster, who novelized “Outland” and “Alien,” and Martin Caidin, the author of such paperback originals as “Marooned,” who novelized “The Final Countdown.”

There is a trend toward hiring authors who are already known to paperback readers. Universal, which packages and edits the novelizations of its movies, hired Gary Brandler, author of the paperback original “The Howling,” to novelize “Cat People” and Hank Searls, who had written several books with sea themes, for “Jaws 2.”

One of the biggest names in novelizations, however, is not an author’s, but a producer’s. Ballantine/Del Rey and the Random House juvenile book division reportedly paid George Lucas more than $1 million for a package of licensing rights to “The Empire Strikes Back,” including calendars, pop-up books, activity books, comic books, special effects books, and even a series of Han Solo novels. There are already 900,000 copies of the novelization of Mr. Lucas’s “Raiders of the Lost Ark” in print, and Judy-Lynn Del Rey is planning such spinoffs as an illustrated film script and a book on the making of the movie.

Peculiarities of Trade

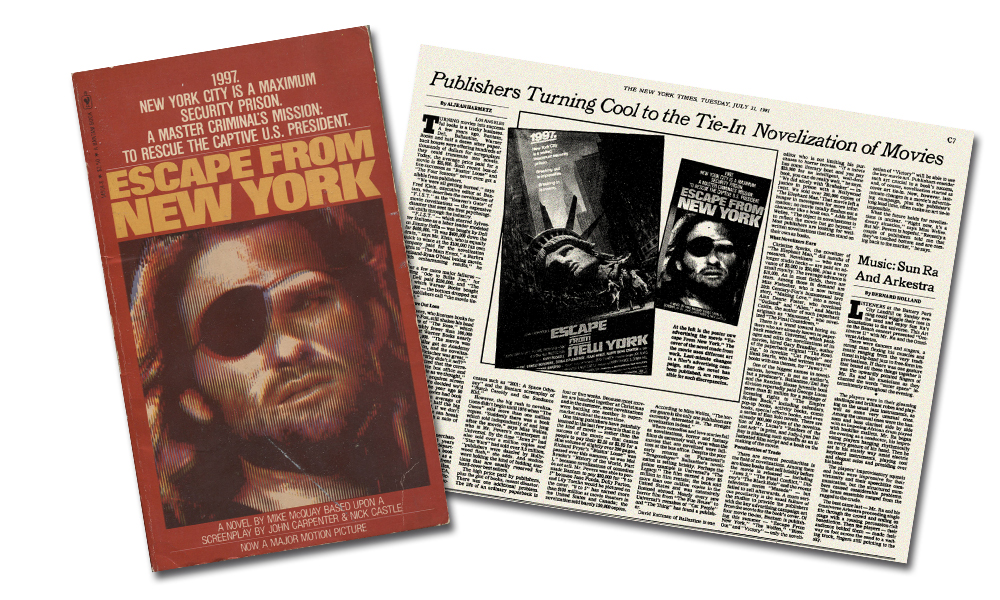

There are several peculiarities in the field of novelizations. Among them are those books that sell briskly before the movie is released – including “Jaws 2,” “The Final Conflict,” Disney’s “The Black Hole” and the recent television series “Masada” – but failed to sell afterwards. A more serious peculiarity is the usual failure of the studios to provide the publishers with the key advertising campaign art from the movie for the book’s cover. Of four movie tie-ins, Bantam is publishing this summer – “Escape From New York,” “The Wolfen,” “Blow-Out” and “Victory” – only the novelization of “Victory” will be able to use the key movie art. Publishers consider such art crucial to a book’s success, and, of course, novelization started as cover art tie-in. Now, however, last-minute changes in a movie’s advertising campaign, plus the publisher’s long lead time, often make an art tie-in impossible.

What the future holds for novelizations is unclear. “Right now, it’s a dreary situation,” says Miss Welles. But Mr. Pevers is hopeful. “Recently a couple of publishers told me that they’ve touched bottom and are coming back to the market,” he says.